BISHOP SERVANT OF THE SERVANTS OF GOD

FOR EVERLASTING MEMORY

TO HIS VENERABLE BRETHREN

THE PATRIARCHS, ARCHBISHOPS, BISHOPS

AND HIS BELOVED SONS

THE PRESBYTERS,

DEACONS AND THE OTHER CHRISTIAN FAITHFUL

OF THE EASTERN CHURCHES

The sacred canons are, according to a summary description given by the seventh ecumenical council of Nicea, those that have been put forth by the divine Apostles, as tradition has it, and by “the six holy and universal synods and local councils” as well as “by our holy Fathers.” Hence the Fathers of the same council, which assembled at the See of Nicea in 787 and was presided over by the legates of our predecessor Hadrian I, confirmed in its first canon “the integral and immutable binding force” of the same sacred canons, “rejoicing over them like one who has found rich spoils.”

Indeed, that same council, when it affirmed that the authors of the sacred canons were enlightened “by one and the same Spirit” and had established “those things that are beneficial,” considered those canons to be a single body of ecclesiastical law, and confirmed it as a “code” for all of the Eastern Churches. The Quinisext Synod had previously done this, assembled in the Trullan chamber of the city of Constantinople in 691, by defining the sphere of these laws more clearly in its second canon.

In the wonderfully great variety of rites, that is, of the liturgical, theological, spiritual, and disciplinary heritage of those churches that have their origins in the venerable Alexandrian, Antiochene, Armenian, Chaldean and Constantinopolitan traditions, the sacred canons are rightly regarded as a notable constituent of that same heritage, constituting a single, common canonical foundation of Church order. Indeed, scarcely, or at least rarely, is there an Eastern collection of disciplinary norms in which the sacred canons–already numbering more than 500 before the Council of Chalcedon–are not enforced or invoked as the primary Church laws established or recognized by an authority that is superior to the same churches. It was always clear to each of the churches that any ordering of ecclesiastical discipline would only be firm if grounded in norms deriving from traditions recognized by the supreme authority of the Church or contained in canons promulgated by it, and that rules of particular law had to conform to the higher law in order to be valid, but that they were null if they differed from it.

“It was through fidelity to this sacred heritage of ecclesiastical discipline that the particular appearance of the East was preserved in spite of so many dire sufferings and hardships which the Eastern Churches have endured both in ancient times and recently; and this was of course not without great benefit to souls” (AAS 66 [1974] 245). These words of Paul VI of happy memory, uttered in the Sistine Chapel during in his address before the first plenary session of the members of the Commission for the Revision of the Code of Eastern Canon Law, recall what was enjoined by the Second Vatican Council concerning “utmost fidelity” in the observance of the said disciplinary heritage by all the churches. These words also echo the conciliar demand that the churches “should endeavor to return to the traditions of their forefathers” in case in certain matters “they have improperly deviated owing to the circumstances of the times or persons” (Decr. Orientalium Ecclesiarum, n. 6).

It is significant that the Second Vatican Council makes it quite clear that “a scrupulous fidelity to the ancient traditions” together with “prayers, good example, better mutual understanding, collaboration and a brotherly regard for what concerns others and their sensibilities” can contribute most to enable the Eastern Churches in full communion with the Roman Apostolic See to fulfill “their special task of fostering the unity of all Christians, particularly of the Eastern Christians” (Decr. Orientalium Ecclesiarum, n. 24) according to the principles of the decree "On Ecumenism."

It should not be forgotten that the Eastern churches that are not yet in full communion with the Catholic Church are governed by the same and basically single heritage of canonical discipline, namely, the “sacred canons” of the first centuries of the Church.

With regard to the whole question of the ecumenical movement, which has been set in motion by the Holy Spirit for the realization of the perfect unity of the entire Church of Christ, the new Code is not at all an obstacle, but rather a great help. Indeed, this Code protects that fundamental right of the human person, namely, of professing the faith in whatever their rite, drawn frequently from their very mother\’s womb, which is the rule of all “ecumenism.” Nor should we neglect that the Eastern Catholic Churches, discharging the tranquility of order desired by the Second Vatican Council, “are to flourish and fulfill their role entrusted to them with a new apostolic vigor” (Decr. Orientalium Ecclesiarum, n. 1). Thus it happens that the canons of the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches must have the same firmness as the laws of the Code of Canon Law of the Latin Church, that is, that they remain in force until abrogated or changed by the supreme authority of the Church for just reasons. The most serious of those reasons is the full communion of all the Eastern Churches with the Catholic Church, in addition to being most in accord with the desire of our Savior Jesus Christ himself.

Nevertheless, the heritage of the sacred canons common to all of the Eastern Churches during the passing centuries has coalesced in a wonderful fashion with the special character of each group of the Christian faithful from which the individual churches are formed and has imbued their entire culture, very often in one and the same nation, with the name of Christ and his evangelical message, which belongs to the very heart of these peoples without reproach and worthy of every consideration.

When our predecessor, Leo XIII, declared at the end of the nineteenth century that “the legally approved diversity of Eastern liturgical forms and discipline” is “an ornament for the whole Church and a confirmation of the divine unity of the Catholic faith,” he considered that this diversity was that to which “nothing else is possibly more wonderful in illustrating the note of catholicity in the Church of God” (Leo XIII, ap. letter Orientalium dignitas, 30 Nov. 1894, prooem.). The unanimous voice of the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council proclaims the same thing, that “the diversity of the Churches united together demonstrates in a very clear fashion the catholicity of the undivided Church” (Const. Lumen Gentium, 23), and “in no way harms the Church\’s unity, but rather declares it” (decr. Orientalium Ecclesiarum, n. 2).

Keeping all these things in mind, we consider that this Code, which we now promulgate, must be considered to be assessed most of all according to the ancient law of the Eastern Churches. At the same time, we are clearly conscious both of the unity and diversity harmonizing to the same end and coalescing, so that the “vitality of the whole Church never appears to be aging. She stands out even more wondrously as the Bride of Christ, whom the wisdom of the holy Fathers recognized as being foreshadowed in the prophecy of David: The queen stands at your right hand, arrayed in apparel embroidered in gold …”(Ps. 44; Leo XIII, ap. letter Orientalium dignitas, 30 Nov. 1894, prooem.).

From the very beginnings of the codification of the canons of the Eastern Churches, the constant will of the Roman Pontiffs has been to promulgate two Codes: one for the Latin Church, the other for the Eastern Churches. This demonstrates very clearly that they wanted to preserve that which has in God’s providence had taken place in the Church: that the Church, gathered by the one Spirit breathes, as it were, with the two lungs of East and West, and burns with the love of Christ, having one heart, as it were, with two ventricles.

The firm and unwavering intention of the supreme legislator in the Church is likewise clear regarding the faithful preservation and accurate observance of all of the Eastern rites derived from the above-mentioned five traditions, expressed in the Code again and again with their own norms.

This is also evident in the various forms of the hierarchical constitution of the Eastern Churches: the patriarchal churches are preeminent among these, in which the patriarchs and synods are sharers in the supreme authority of the Church by canon law. With these forms, delineated in their own title at the opening of the Code, there is immediately evident both the appearance of each and every Eastern Church as it has been sanctioned by canon law and their autonomous status, as well as their full communion with the Roman Pontiff, the successor of Saint Peter, who, presiding over the whole assembly of charity, safeguards legitimate diversity and, at the same time, keeps watch that individuality serves unity rather than harming it (cf. const. Lumen gentium, n. 13).

Furthermore, in this area full attention should be given to all those things that this Code entrusts to the particular law of individual Churches sui iuris, which are not considered necessary to the common good of all of the Eastern Churches. Our intention regarding these things is that those who enjoy legislative power in each of the churches should take counsel as soon as possible for particular norms, keeping in mind the traditions of their own rite and the precepts of the Second Vatican Council.

The faithful protection of the rites must clearly be in conformity with the ultimate goal of all the laws of the Church, which is set forth in the economy of the salvation of souls. Therefore, this Code has not accepted anything that has lapsed or was superfluous in previous legislation, or that is not suited to the region or the necessity of the times. But in establishing new laws those things were uppermost in our mind which really responded in the best way to the desired economy of the salvation of souls in the richness of the life of the Eastern Churches, while displaying a coherence and agreement with sound tradition. This was set out, according to the direction of our predecessor Paul VI, at the beginning of the work of revising the Code: “new norms should appear not, at it were, as a foreign body intruded into an ecclesiastical structure, but like a spontaneous blossoming from already existing norms” (AAS 66 [1974] 246).

These things become splendidly clear from the Second Vatican Council, since that Council “brought forth from the treasury of tradition what is old and what is new” (ap. const. Sacrae disciplinae leges, AAS 75 [1983] Part II, XII), by carrying over into newness of life the tradition from the Apostles, through the Fathers, everywhere integral to the message of the gospel.

The Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches should be considered as a new complement to the teaching proposed by the Second Vatican Council. By the publication of this Code, the canonical ordering of the whole Church is thus at length completed, following as it does the Code of Canon Law of the Latin Church, promulgated in 1983, and the “Apostolic Constitution on the Roman Curia” of 1988, which is added to both Codes as the primary instrument of the Roman Pontiff for “the communion that binds together, as it were, the whole Church” (ap. const. Pastor bonus, n. 2).

But now if we turn our attention to the first steps of the canonical codification of the Eastern Churches, the Code appears as a port, reached after a voyage of more than sixty years. For this is a body of laws in which all the canons of ecclesiastical discipline common to the Eastern Catholic Churches are first collected together in one place and promulgated by the supreme legislator in the Church. This has taken place after the many, great labors of the three commissions instituted by that legislator; the first of these was the “Cardinalatial Commission for Preparatory Studies on Eastern Codification” erected in 1929 by our predecessor Pius XI (AAS 21 [1929] 669), under the presidency of Cardinal Pietro Gasparri. The members of this Commission were Cardinals Luigi Sincero, Bonaventura Cerretti and Franz Ehrle, with the assistance of the secretary, Bishop (later Cardinal) Amleto Giovanni Cicognani, an assessor of the “Sacred Congregation for the Eastern Church,” as it was then called.

The work of two groups of experts, for the most part taken from the heads of the Eastern Churches, was of great importance, as a matter of fact, to the preparatory studies; this work was brought to completion within six years (cf. L\’Osservatore Romano, 2 April 1930, p. 1). When the death of Cardinal Pietro Gasparri intervened, it was decided to continue by constituting the “Pontifical Commission for the Codification of the ‘Code of Eastern Canon Law.’” This commission was erected on 17 July 1935 to determine, as its title indicated, the text of the canons and to supervise the composition of the “Code of Eastern Canon Law.” It should be noted in this regard that the Supreme Pontiff himself, in the Notice of the institution of the Commission which appeared in the official commentary Acta Apostolicae Sedis (AAS 27 [1935] 306 – 308), determined that the title of the future Code was to be enclosed in quotation marks, to indicate that, although it was the best, it was selected “until a better could be found.”

The presidents of the “Commission for the Codification of the ‘Code of Eastern Canon Law’" were Cardinal Luigi Sincero, until his death; Cardinal Massimo Massimi; and, after his death, Cardinal Gregory Peter XV Agagianian, the Patriarch of the Armenian Church.

Among the cardinals who were, along with the president, made the first members of the Commission, namely, Eugenio Pacelli, Julio Serafini, and Pietro Fumasoni-Biondi, the name of Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli stands out. Later on, by the great providence of God, he brought to completion, in his great solicitude for the good of the Eastern Churches, almost the whole work of canonical codification as Vicar of Christ and Pastor of the whole Church. For, of the twenty four titles with which the Code of Eastern Canon Law had been put together in the aforesaid Commission by his will, he promulgated no less than ten, of more urgent importance, by means of four apostolic letters motu proprio (Crebrae allatae sunt, Sollicitudinem nostram, Postquam apostolicis litteris and Cleri sanctitati). The rest, approved at the same time by the cardinal members of the Commission and for the most part already printed with a pontifical mandate “for promulgation,” but, coming at the end of that pontificate and at the same time as John XXIII, his successor in the chair of Saint Peter, called the Second Vatican Council, remained in the archives of the Commission.

However, with the passing of years, until the conclusion of that Commission in the middle of 1972, the college of members was increased by pontifical mandate as several cardinals performed their work with diligence, with other members succeeding those who had died. After the Second Vatican Council was finally concluded, all the patriarchs of the Eastern Catholic Churches were added to the Commission in 1965. But by the beginning of the final year of the Commission for the Codification of the Code of Eastern Canon Law, the college of members consisted of the six heads of the Eastern Churches and the Prefect of the Congregation for the Eastern Churches.

Also, from the very beginning of the Commission for the Codification of the Code of Eastern Canon Law, and for a long time thereafter, Father (later Cardinal) Acacio Coussa, B.A., served as its secretary and labored with great zeal and wisdom. We remember him here with praise, along with the distinguished consultors of the Commission.

The constitution and form of the Pontifical Commission for the Revision of the Code of Eastern Canon Law, established during the middle of 1972, safeguarded its Eastern character, since it was composed from the multiplicity of Churches, with the Eastern patriarchs being elevated in the first place. But the work of the Commission kept in mind its collegial character, for the canons, formulated by groups of expert men chosen from all of the Churches, and worked out gradually, were sent to all the bishops of the Eastern Catholic Churches before all others, so that they might give their opinions in a collegial fashion, insofar as this was possible. Later on, these drafts, revised repeatedly in special study groups according to the wishes of the bishops, after a diligent examination by the members of the Commission and further modified if the case warranted, were accepted by the general consent of votes in a plenary meeting of the members in November 1988.

We must truly recognize that this Code is “the work of the Easterners themselves,” according to the wishes of our predecessor Paul VI expressed in his address at the solemn beginning of the Commission\’s work (AAS 66 [1974] 246). We are deeply grateful to each and every one of those who participated in this work.

Among the first, we thankfully remember the name of the late Cardinal Joseph Parecattil of the Malabar Church, who served with distinction as president of the Commission for the new Code for almost the entire time, except for the last three years. Together with him, we remember in particular the late Archbishop Clement Ignatius Mansourati of the Syrian Church, who served as vice-president of the Commission in the first, particularly difficult years.

It is a pleasure also to mention the living as well: in the first place, our venerable brothers Miroslav Stephan Marusyn, now appointed as archbishop and secretary of the Congregation for the Eastern Churches, and who served for a long time in a distinguished manner as vice-president of the Commission, as well as Bishop Emile Eid, the current vice-president, who brought the work for the most part to a happy conclusion; after these we remember our beloved Ivan Žužek, a priest of the Society of Jesus, who labored with assiduous zeal as secretary of the Commission from the very beginning, and the others who were valuable parts of the Commission, whether as members, the patriarchs, cardinals, archbishops and bishops, or else as consultors and co-operators in the study groups and in other functions. Finally, we recall the observers, invited from the Orthodox Churches for the sake of the desired unity of all the Churches, who were a great assistance by their useful presence and collaboration.

We have great hope that this Code “will be translated happily into the action of daily life” and “will furnish a genuine testimony of reverence and love for ecclesiastical law,” as Paul VI of blessed memory had hoped (AAS 66 [1974] 247), as well as establishing that same order of tranquillity among the Eastern Churches, so clear in antiquity, that we desired with an ardent spirit for the entire ecclesial society when we promulgated the Code of Canon Law for the Latin Church. This is a matter of order, “which, granting the primacy to love, grace and charism, at the same time facilitates their ordered development both in the life of the ecclesial society and even in the lives of the individuals who belong to it” (AAS 75 [1983] Part II, XI).

“Let joy and peace, with justice and obedience, commend” this Code as well, “and let that which is commanded by the head be observed by the members” (ibid., XIII), so that, with everyone\’s united strength, the mission of the universal Church may increase, and the kingdom of Christ the “Pantokrator” may be more fully established (cf. John Paul II, Allocution to the Roman Curia, 28 June 1986, AAS 97 [1987] 196).

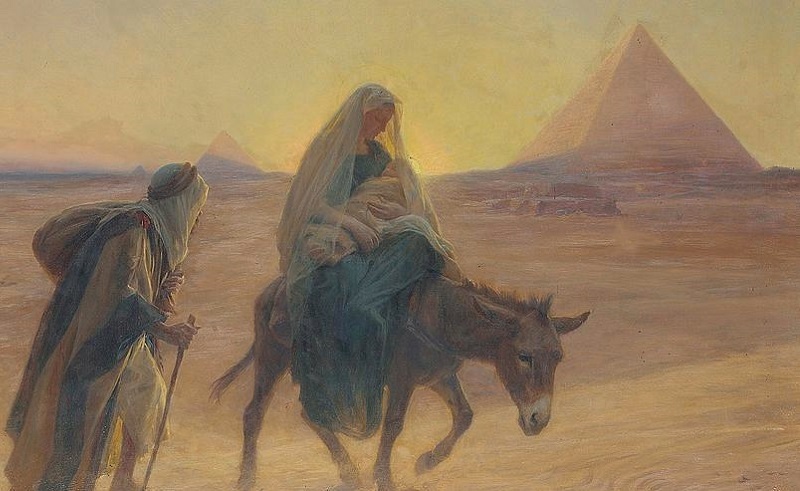

We beseech the holy ever-Virgin Mary, to whose most tender protection we have repeatedly commended the preparation of this Code, to ask her Son with a mother\’s plea that this Code may become a vehicle of that love which must be inwardly fastened in the heart of every human creature: this is the love that was so splendidly drawn forth from the heart of Christ after it was pierced by a lance on the cross, according to that outstanding witness, Saint John the Apostle.

Therefore, having called upon the assistance of divine grace, sustained by the authority of the blessed apostles Peter and Paul, with full knowledge and assenting to the requests of the patriarchs, archbishops and bishops of the Eastern Churches, who have cooperated with us in collegial affection, making use of the fullness of the apostolic power with which we are endowed, by means of this our constitution we promulgate the present Code as it has been arranged and revised, to have force from this time forward. We decree and order that it is to have the force of law for all Eastern Catholic Churches from now on, and we entrust it to the hierarchs of those Churches to be kept with care and vigilance.

However, so that everyone to whom this pertains may have a close examination of the prescripts of this Code before they come into effect, we declare and decree that they come into force on the first day of October 1991, on the feast of the Patronage of the Blessed Virgin Mary in many Churches of the East.

Anything else to the contrary whatsoever, even worthy of most special mention, notwithstanding.

We therefore urge all our beloved children to carry out these indicated precepts with a sincere intention and a ready will; you should be certain that the Eastern Churches will have the greatest possible regard for the good of the souls of the Christian faithful with a zealous discipline, that they may flourish more and more, and discharge the function entrusted to them, under the protection of the blessed and glorious Virgin Mary, who is truly called “Theotokos” and shines forth as the exalted Mother of the universal Church.

Given in Rome at Saint Peter\’s, on 18th day of October, in the year 1990, the thirteenth of our pontificate.

POPE JOHN PAUL II